Zhao Dunhua: A glimpse into his philosophical mind and educational vision

Oct 20, 2020

Peking University, October 20, 2020: Following his nomination, Zhao Dunhua was rewarded the 2020 Teaching Achievement Award on 24th August in honor of his significant contributions to Peking University as a senior professor at the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies. At Peking University, the Teaching Achievement Award manifests the highest recognition of a teacher’s educational accomplishment. Zhao was one of the five teachers who has received the honor after its initiation in 2018.

Zhao Dunhua

Zhao Dunhua

Zhao commented that the prize was both an acknowledgement of what he has achieved over the course of his teaching career, while also propelling him to achieve greater accomplishments in the future. He believed his teaching career is still an ongoing process with lots of room left to accomplish other progress and innovations. Zhao suggested that in the ever-changing modern age we now live in today. Philosophers are the ones endowed with the ability to recognize the morality and truth behind everything we see. In the face of global challenges, philosophers from Peking University were entitled to help others perceive things in a different light, as well as marking their own ground within the world of philosophy.

Zhao’s philosophy career

Zhao Dunhua’s first encounter with philosophy took place at the library of his junior school when he was fifteen years old. As a frequent visitor to the library, he occasionally found two volumes of a book series called Outline of Great Books, which were Chinese translated versions of Sir John Alexander Hammerton’s original works in English. Zhao was especially fascinated by the volume concerning philosophy and social science, which provided a chronological overview of western philosophy from Plato and Aristotle to Nietzsche. Many things that were discussed in this book confused Zhao. Due to a lack of other references, Zhao read the book multiple times, with several questions remaining unsolved. As Aristotle said, “Philosophy begins with Wonder”. From then on, Zhao subconsciously took his first steps on the journey of philosophy, lead completely by his wonder.

In 1977, Zhao Dunhua was admitted to the Department of Chinese Language and Literature in Fuyang Normal University. Chinese was not Zhao’s first choice. He preferred to study philosophy. However, since higher education just restarted around that time in China, Zhao had to cherish the opportunity that granted him a post-secondary education. Reminiscing back to his youth, Zhou recalled that “whatever the major is, as long as I can get access to more books in the University, I’m happy”.

Once school began, Zhao decided to learn western philosophy by himself. As China started the economic reform in 1978, people paid more attention to western civilizations and culture, which led to more and more books on western philosophy being published in China. Zhao grasped the opportunity and began reading extensively on western philosophy. Whenever he had spare time, he went to the library for books concerning philosophy. His favorite was a four-volume series called Selected Readings of Western Classical Philosophy, edited by the Institute of Foreign Philosophy in Peking University. Considering that Peking University had one of the best faculty of philosophy in China at that time, Zhao intended to apply for the postgraduate program of philosophy at Peking University.

Zhao’s target university changed when he saw the introduction of a joint education program offered by the Department of Philosophy of Wuhan University. At that time, Wuhan University created a joint program which allowed postgraduate students to study at both Wuhan University and one of their partnered universities. The department of philosophy of Wuhan University gathered two scholars from PKU named Chen Xiuzhai and Yang Zutao, who were sent to Wuhan to lead the program. Finding the program tailored for himself, Zhao Dunhua sent his application to Wuhan University. With his determination, diligence, and strong learning habits, Zhao was admitted by Wuhan University and successfully became the student of Chen Xiuzhai.

Chen was one of the editors of Selected Readings of Western Classical Philosophy. He told Zhao that due to the lack of experts who exceled at Medieval Philosophy, the era of philosophy in the Middle Ages remained blank in Western philosophy that was taught in China. He found Zhao a promising student, and hoped he could fill in the gap of Medieval Philosophy studies in China. With Chen Xiuzhai’s advice in his mind, Zhao chose the Catholic University of Leuven, or “KU Leuven” for short, in Belgium as his target university for a master’s degree, which was known for its Medieval Philosophy studies.

Once Zhao was admitted however, things were proven to be much harder than it seemed. As it turned out, KU Leuven required Zhao to get a Bachelor’s Degree in Philosophy prior to continuing higher levels of study. It took Zhao one year to fulfill all the undergraduate courses in Belgium, which he condensed from the otherwise 4 years of a regular BA program. The workload in the University of Leuven was heavy, and students were provided only one chance to take the final examinations. Many students failed to pass the assessments for the degree. As the only Chinese student out of more than 30 students in the program, Zhao had to handle another obstacle as well— learning his courses in English.

July 1983, Zhao with Chen Xiuzhai at KU Leuven

When Zhao first started learning English at Fuyang Normal University, English education was under-developed in China. Zhao’s English abilities were mostly self-taught. He bought an English-Chinese dictionary and recited each term. Though he built his vocabulary and improved reading with this method, he still had trouble listening due to the lack of an English-speaking environment. When he arrived at KU Leuven, he found it really hard to catch up and understand others, especially when people were talking quickly. Fortunately, one of his American classmates who often lent him his class notes, Zhao was then able to keep pace with others. In the end, Zhao’s strong self-studying abilities and perseverance led him to his victory, of passing the strict assessment at KU Leuven with excellent performance, which granted him the BA degree he had longed for. During his second year in Belgium, Zhao found that he could easily follow the teachers in class. He then took master’s courses, which afterwards led to his Master’s Degree, and soon he continued on with his PhD as well. In the end, Zhao’s PhD dissertation was rated as one of the best in the year he graduated.

1988 was a year of opportunities, and for Zhao particularly, it was a year when he decided to return to his home country. Most Chinese students who had been sent abroad to attend higher education chose to remain in Europe or transfer to the United States to seek different future paths, however this never crossed Zhao’s mind, as he always remembered the founding reason why he was given the opportunity to study in KU Leuven - to educate Chinese students about medieval philosophy, which remained a crucial gap missing in the timeline of Western philosophy being taught in China.

On People’s Daily, he saw that Peking University was recruiting philosophy scholars. Zhao applied the job and soon received the offer. In September of 1988, Zhao became the first overseas PhD student who arrived at the Philosophy Department in PKU.

Becoming a part of the PKU community was a dream come true for Zhao, who once dreamed of attending school at one of the top universities in China. Back when he was completing application forms for his university preferences, the Philosophy Department at PKU was his first option. Years later, as he embarked on his first step into campus, Zhao immediately realized that this was the place where he belonged. At PKU, a land full of academic atmosphere and creative vitality, Zhao found his surroundings a place of solace and motivation, which motivated him to rewrite some chapters of his doctoral dissertation into a book about Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein, an Austrian philosopher. The book was published in 1989 by the Sanlian Publishing House of Hong Kong, which received appraisal from Hong Qian, who was a well-known philosopher in China. Zhao’s encounter with Hong Qian was eventually extended beyond the brief exchange regarding the published book, as they became long-lasting scholastic companions for the remainder of Zhao’s career. Now looking back, Zhao remembered the day when he first met Hong in person. He was immediately greeted with a warm welcome and before they both realized, the first conversation they had turned out to be the first of many in the impending future. In 1992, when Hong Qian was admitted in hospital due to serious illness, Hong held Zhao’s hands for the first time and earnestly told Zhao to continue developing philosophical pursuits in China. The scene near the hospital bed would continue to propel Zhao forward in all his future scholastic endeavors, as it was a memorable point in his life where he truly felt duty-bound to the future of philosophical education in PKU and in China as a whole.

Zhao, of course, did not let his mentor down. In 1991, his book Karl Popper was published, inspired by the visits he had with Popper himself back when he was at KU Leuven. During his conversations with Popper, he gathered countless valuable insights, which he organized and concluded in his book. Karl Popper received nationwide attention, enabling readers to be introduced to the Vienna Circle, of which Popper was an integral part of. The book published before Karl Popper, named The Interpretation of Rawls’s “A Theory of Justice”, was also written by Zhao himself, and was the first Chinese book to have translated and analyzed John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice.

Popularizing Western philosophy among Chinese students

Once he settled into his role of becoming a lecturer at PKU, Zhao also created courses based on The History of Western Philosophy and Contemporary Western Philosophy, as well as writing a book named A Brief History of Western Philosophy, which has become the assigned textbook used for mandatory philosophy courses at PKU to this day. Upon his establishment of these two courses, Chinese philosophy students were finally introduced to medieval philosophy, thereby fitting in the missing piece that once existed in the teaching of contemporary Western philosophy to Chinese students.

“Medieval Philosophy”, a series of philosophical books written by Zhao

Zhao’s solid studying habits and innovative teaching methods, as well as worldly academic experience enabled him to quickly become a popular lecturer among students. In 1990, he was assigned to be an associate professor. Two years later, he rose to the role of as a tenured professor with additional funding sponsored by the government. In 1993 he was chosen as one of the most renowned philosophy professors in the nation, and was appointed the vice-dean of the Philosophy Department at PKU.

In 1993, Zhao wrote another prominent piece of philosophy work, named Christian philosophy of the Past 1,500 Years. Publishing this piece was the fruitful result of Zhao’s painstaking efforts over the years; a reward to all the studious and lonely nights he had spent studying medieval philosophy at KU Leuven. The grand mission that was once bestowed upon Zhao - to study the medieval era that was missing in the Western philosophy curriculum in China, was finally filled up and answered upon the publication of his new book. The work was published in Chinese mainland and Taiwan at the same time, receiving critical acclaim from both nationwide and international scholars. It was reprinted in 1995.

Following the success of his book on medieval philosophy, Zhao diverted his focus on the comparison between Chinese and Western philosophy. The difference that exists between the two, Zhao said, would be the way Western and Chinese philosophy approaches their way of understanding the world and its subsequent issues. For instance, Chinese philosophy such as Confucian, Daoist and Buddhist approaches to understanding the world are in terms of their relationships to other things and ultimately to the whole picture which contains them. Nowadays, Chinese philosophy often converges philosophical ideologies and concepts from traditional Chinese cultural influences, contemporary Western philosophy and Marxism (which stems from Western philosophy but is now transformed into a more Chinese-centered philosophical model). On the other hand, western philosophy tends to focus more on finding the truth and logic, providing insights on discovering the origin of all things in the universe. Whereas Chinese philosophy emphasizes collectivism, Western philosophy targets individualism. Zhao believes that by educating Chinese students on both philosophical models, students would develop a deeper understanding on their course materials, and relate them to real life issues existing in our society today. With examples such as AI technological advancements’ effect on humanity, and many more.

As an established philosophy professor at PKU, Zhao regarded philosophy as a medium where numerous fields crossed paths; an interdisciplinary field where the old collides with the new, a place where many seeks to find the truth behind many aspects in our society today. As a renowned philosophy professor, Zhao believes that now is the time for a reformation in philosophy. Philosophy, with its long-lasting history in various parts of the world, has to be prepared for innovation in all aspects, whether it be its ideology, teaching methods, or integrating with other fields of study that are gradually emerging in the modern age. Zhao wishes to establish cross-field studies, open studies, or interdisciplinary studies for philosophy students to utilize the knowledge they have learned in textbooks and apply them in real-life situations.

Zhao is now widely-known as an expert on medieval philosophy, but as an educator, he is knowledgeable in nearly every field in philosophy, as well as being an acclaimed professor with a specific teaching style showcasing his principles in the classroom. In 1999, Zhao was rewarded with the PKU Teaching Award. When asked about his teaching concepts and techniques, Zhao stated that it is essential to have teachers take initiatives during class discussions, and guide students throughout the process of learning. Currently, there are teaching styles that emphasize more on student-oriented participation during intro-level courses, however those methods would not be applicable when students are not familiar with the course material. For bachelor students attending introductory philosophy courses, especially courses regarding western philosophy, teachers should act up to the role as the questioner, ask students questions and providing answers to them after. During seminars, whether it be class reports or presentations, teachers should lead students to more in-depth discussions, enabling students to perceive things with a bigger perspective. Teachers would also need to conclude and point out the important components of each discussion. For masters and PhD students on the other hand, teachers should lessen their participation in class discussions and enable students to form their individual opinions and thesis. Zhao believes that once students have become familiar with the basics of philosophy, teacher can then gradually let go and allow students take the lead of their own journey through the vast and sophisticated world of philosophy.

Special bond with PKU

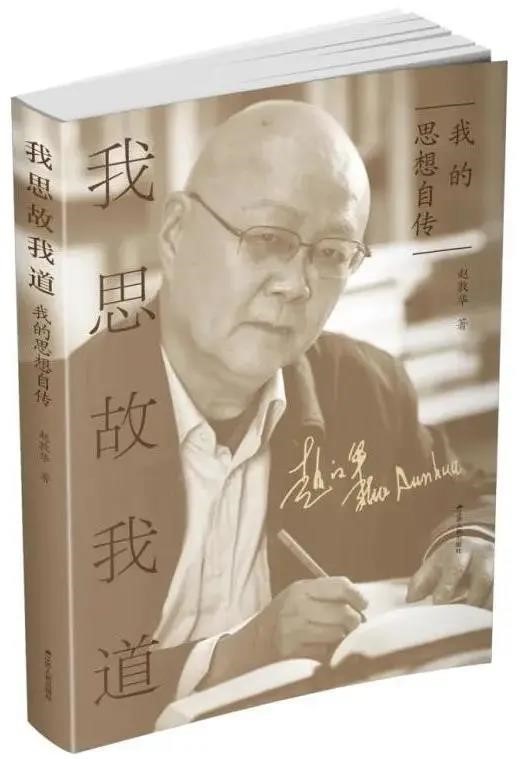

《我思故我道》, an autobiography written by Zhao, soon to be published in 2020

PKU, being one of the most notable universities in China, holds the highest level of prestige even by name. For many students and staff members, the honor of being a part of PKU’s culture and community is in itself an incredible honor to have. This, subsequently, leads to many heated discussions regarding the identity of being a true PKUer.

What makes a person a true PKUer has always been a subject of interest and endless debate among every single person who’s ever been associated with the school. Zhao, seeing all this unfolding in front of eyes, couldn’t help but re-evaluate his status as a PKU professor. Could he define himself as a PKUer? Judging by his schooling years, he would no doubt be unqualified, since he never attended school at PKU, which ironically was where he spent the vast majority of his life at.

Would teachers be considered as PKUers? Many might wonder. After years to contemplation, Zhao came up with an answer to his own question. For so long, he has dabbled with his identity, he noted, of trying to define his place in PKU which he has long considered as his second home. When answering questions regarding his PKU self, he said, at the end of the day, it would not matter why or how others define you, because it all becomes tedious baggage afterwards left with little value. Things that matter would unveil its worth at the end, and to Zhao, he sees his value as a PKU professor when students he’s taught for years has achieved success in their respective careers, or when he witnesses young students become enlightened with the blink of an eye from a class he’s taught for the hundredth time. His identity as a PKUer is reflected by his students, his books, his lessons, and the very spirit he embodies - the will to observe the world around us with inclusiveness, question the facts presented before us, and learn with a heart full of wonder.

Reported by: Rose Li, Fan Xueyuan

Edited by: Zhang Jiang

Photo credit to: Liu Yueling, Zhao Dunhua

Sources:

Interview Material from September 24th, 2020

pkunews.pku.edu.cn/xwzh/2007-04/27/content_113829.htm

http://www.aisixiang.com/data/110473.html

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/3-JKxAXdDk2aYMwd_k0bsw