News & Events | About PKU News | Contact | Site Search PKU Today in History - a daily column featuring historic events regarding PKU and PKUers.

Peking University, Apr. 29, 2011: On this day 43 years ago, a “rightist” Peking University student was executed for refusing to confess herself a “counterrevolutionary” during the "Cultural Revolution" (1966-76). Her name was Lin Zhao.

Born on December 16, 1932 as Peng Lingzhao, Lin Zhao was the eldest child of a prominent family in Suzhou, Jiangsu province. From her teenage years, Lin was keen on revolution. She once ran away from home to attend Sunan Training School for Journalism, the center of communistic thoughts, in 1949, and changed her surname to show her resolution of undertaking the cause of revolution while turning down tradition's chains that blind her.

In the autumn of 1954, Lin was matriculated by the Department of Chinese Language and Literature at Peking University with the highest score in college entrance examination in Jiangsu province, and majored in journalism. Like other newly-arrived students, Lin shared with the age’s animation, hopefulness and political enthusiasm brought about by the founding of New China.

Lin stood out on campus for her writing talent and outspoken and sharp utterances. She aspired to become one of the first generation of women journalists in new China. In 1955, she joined PKU Poets’ Society, serving as editor of its publication, and later turned member of the editorial committee of Red Mansion, a student journal of literary and artistic creation.

"Her life was poetic," recalled Xie Mian, Lin's fellow at the society who later turned a senior professor of Chinese literature at PKU.

Noted for her hometown in Suzhou, her talent for poetry, and her soft coughs (caused by slight phthisis) from time to time, Lin was constantly bantered as Lin Daiyu in the popular Chinese novel Hongloumeng (Dreams of the Red Mansion). Five decades later, Lin’s close friend Zhang Lin still well remembered her willowy figure. “We all called her Little Girl Lin. Her graceful gait always reminded me of the beautiful verses describing Lin Daiyu in the novel,” said Zhang during an interview.

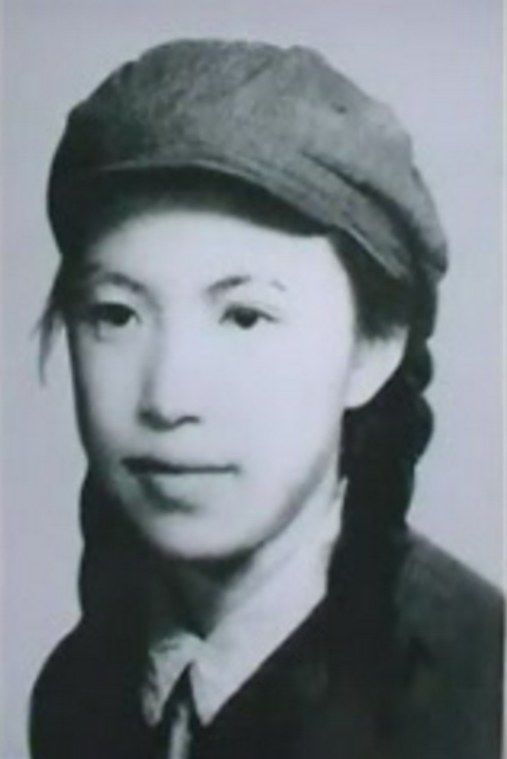

A portrait of Lin Zhao (File photo)

But Lin was not the touchy, delicate maiden in the ideal Daguan Yuan (Grand View Garden). By her entrance into PKU, Lin had, to some degree, achieved her political maturity, not in temporizing, but in thinking independently and with clairvoyance. This usual combination of enthusiasm and cool-mindedness had a bearing on her previous experiences in which she was compelled to fabricate evidence of her mother’s guilt in order to satisfy the demands of the revolutionists. She regretted bitterly over what she had done to her mother and to her own principle. Although she still possessed great passion for the socialistic cause, she determined that she would never again act in a radical manner, following the trend blindly. Her maturity and adherence to conscience distinguished as well as victimized Lin in a more radical rectification campaign soon to come.

In 1957, the "Hundred Flowers Movement" in which the CPC encouraged criticism of and solutions to national policy issues, started. Many students presented their suggestions in the form of dazibao, i.e., big-character poster. Lin openly supported her classmate Zhang Yuanxun’s dazibao "It’s the Time!," but was labeled as a “rightist” favoring “capitalism.” During the following “Anti-rightist Campaign,” Lin felt agonized and perplexed when she saw some of her classmates labeled as “devil” and “lunatic” due to their straight speech. She attempted suicide to protest against the charge, but was found out and saved. When she came to herself, she shouted: “I will never lower my head to the unfair sentence!” The consequence of this protest is an aggravation of her “crime.” Lin was sentenced to a three-year "re-education through labor" (RTL) at the journalism library, Renmin University of China.

In the press library, Lin’s phthisis worsened. In 1959, she was permitted to be taken home to receive medical treatment in Shanghai. During her convalescence, Lin founded The Spark magazine with some youths who were also wrongly labeled as “rightists” in order to express their dissenting opinions about the extremism in the Great Leap Forward, which they perceived as against the trend of historical development. After some research, they even planned to write a formal letter to the leading organ in hope of correcting some of the wrong policies. These were extremely dangerous acts at that time. The result of these efforts was their being arrested as "counterrevolutionary clique” in 1960. “We certainly knew the danger,” said one member of the "counterrevolutionary clique” Gu Yan. “We knew in printing the pamphlets we were risking our life, but we simply could not stand by. If no one dares to stand out to defend the truth, the people are depraved of all hope."

Lin was sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment in Shanghai Tilan Bridge Prison. Faced with maltreatments, Lin frequently conducted hunger strikes and attempted suicide to protest. She always wrote to her family asking for more white sheets. They didn’t know her intention until Lin was released on medical parole in early 1962 when her mother found out all the scars on Lin’s arms. In fact, Lin had split the white sheets into straps and wrote poems and articles with her own blood on them. Her pen had been taken away; so she pierced her skin with her hairpin and wrote with the hairpin in her blood. In late 1962, Lin was arrested again for her continuous dissenting activities. During her stay in prison, Lin had altogether written 200,000 words’ works of blood, including diaries, political manifestos, poems and petition letters, which displayed her determination to hold firmly to the truth and her outspoken rights to freedom.

Because of her persistent resistance to confess her “crime” and to be “re-educated,” Lin was finally sentenced to death. She was executed on April 29, 1968, at the age of 36. When Lin’s mother realized Lin’s death, she went mad and died of indefinite reason several years later. As for Lin’s father, he committed suicide right a month after Lin’s second arrest. He knew his daughter and her unavoidable doom. For Lin’s part, however, she never worried about her destiny. In her poems she always called herself a “martyr” for the cause of freedom. In Lin’s final work, she wrote that “history will proclaim my innocence.” And it did. In 1980, the Shanghai Higher People’s court overthrew the accusations imposed on Lin Zhao.

"I am a sword! I am a flame!” – this is Lin’s declaration and a depiction of her disposition.

Written by: Yan Binghan

Edited by: Chen Miaojuan

Source: Agencies